BÉRANGER has written few more stirring lyrics than the "Chant du Cosaque," and one of the many illustrators of the works of the great French "chansonnier" has prefixed a most alarming picture to this particular song, representing the Cossack, fiercely bearded and with his sheepskin mantle trailing in the wind, brandishing his lance in one hand and his whip in the other, while he urges his fiery steed, or rather pony, over a mass of broken columns, crowns, regal robes, swords, crucifixes, rosaries, mitres, and caskets of jewels. The burden of the song is certainly spirited if somewhat formidable, "Neigh! neigh! with pride, my faithful courser, And trample kings and nations under foot!" The notion which BÉRANGER strove to inculcate in this wild ode was a purely Republican one. He was impressed when, during the Restoration, he penned the poem by the idea that the prodigiously numerous democracy of Russia would ere long burst its bonds, and that a new ATTILA, typified by his Cossack, would spread an avalanche of barbaric hordes all over Western Europe, and produce universal anarchy, in the midst of which might be planted the tree of true liberty. Seventy years, however, have passed, and the Cossacks, both of the Don and the Ukraine, the Ural and the Caucasus remain faithful to the Czar, and are indeed the most useful corps of light cavalry for warlike purposes and military police that the Autocrat can coerce his subjects withal in times of peace; while, oddly enough, the Cossacks, once so cordially detested in France, are now petted and made much of by advanced French Republicans, who would be very glad to see those warriors trampling Germany under foot, but would strongly object to the bearded cavaliers, with the Astracan caps and the long lances, invading French territory. Meanwhile the Cossack has not been an exclusively stay-at-home individual. He has not, it it true, shown himself on horseback and in full warlike panoply on the Boulevard des Italiens or in the Champs Elysées since the year 1815; still, it is interesting to learn that last Sunday, among the congregation at St. Paul's Cathedral, was to be seen a detachment of "Caucasian Cossacks," who, in company with a small band of Sioux and other Indians, and escorted by some Wild West cowboys, attended Divine service. The Cossacks, ten in number, are under the command of their Hetman, Prince IVAN MAKHARADZE, an exalted designation which need excite but little astonishment, seeing that there are several districts in Southern Russia in which the male natives are all princes; and that princely rank is often possessed by the Tartars who officiate as waiters in the hotels and restaurants of Moscow and St. Petersburg—only they drop their titles when they shave themselves, and assume the sable garb and white cravat of the waiter, resuming it when they return to their native steppes, let their beards grow, and enwrap themselves in their beloved sheepskin cloaks.

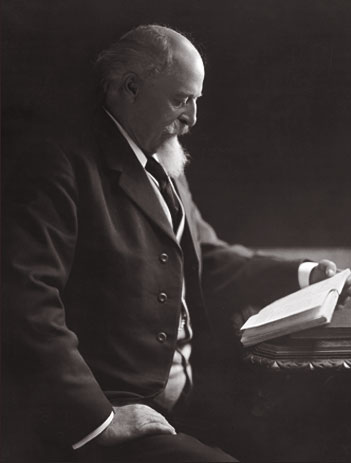

Prince IVAN MAKHARADZE'S visit to this country with his select "pulk" of Cossacks is one of an eminently pacific character. These natives of the Wild South, who have come from some part of the extensive region between the Black and the Caspian Seas, are, of course, daring and dexterous riders, who vindicate to a brilliant extent their historic fame as horsemen. They have, apparently, not brought their own shaggy, hardy, savage little steeds with them; but at Earl's-court, where they form part of Buffalo BILL'S Wild West entertainment, they perform their marvellous feats in the saddle while mounted on Indian ponies, which, taken as equine acrobats, may dispute the palm with Mexican mustangs and Australian buck-jumpers. It happens, however, that the Hetman MAKHARADZE and his troop are not the first Cossacks who have visited the British Metropolis. During our long war with NAPOLEON, at the beginning of the century, we had on one occasion to offer hospitality to a very large corps of Russian infantry, who had been fighting the French in Switzerland, and these Muscovite hordes were quartered in the Isle of Wight. At another period, a strong contingent of Russian troops were billeted as friends on the town of Chatham; but the most picturesque aspect of Russian military character visible in England was when the famous Hetman PLATOFF came to these shores, in the train of the Allied Sovereigns, in 1814. PLATOFF, who was not a Prince, but only a Count, was about fifty years of age at the end of the Napoleonic war. His dashing valour in the field, and his acknowledged skill in handling light cavalry, had rendered him in the highest degree useful to his Sovereign, the Czar ALEXANDER I.; and in the Imperial army his local rank of Hetman was held to be equivalent to that of a Lieutenant-General. Beyond his great bravery and capacity as a commander of cavalry, there would not appear to have been anything very remarkable about the Hetman PLATOFF. He had a rooted dislike of soap and water; he was immoderately fond of corn brandy; and he rather encouraged than dissuaded his ferocious followers to plunder every French village they passed through, and to eat up all the tallow candles and drink up all the train oil they could lay hands upon. Yet when PLATOFF arrived in Paris he was lionised to an almost unprecedented extent in the most fashionable French society, which naturally, after the fall of the Empire, sympathised deeply with the savage warriors who in the retreat from Moscow, and at Leipsic, had done so much to shatter the power of BONAPARTE. Invitations to dinners, balls, and suppers flowed in on the Hetman PLATOFF, who tried to make himself as agreeable as he could to his distinguished hosts; and in LOCKHART'S "Life of Scott" there is an amusing story told of how the Hetman, espying Sir WALTER in one of the Parisian thoroughfares, leapt from his horse and impassionately embraced the illustrious poet and novelist, the ingenuous Cossack chieftain being under the impression that Sir WALTER had not only written "The Lay of the Last Minstrel," but that he was the Last Minstrel himself.

The Hetman was not the only Cossack who honoured London with his presence in the great year of European peace. A venerable lady, once well known in English society, used to tell her son how she could remember, as a young married woman, in 1814, attending a grand ball at a palatial mansion in Grosvenor-square, to which the Allied Sovereigns and the more conspicuous members of their suites had been invited. Among the guests was the Hetman PLATTOFF, who for the time had overcome his fondness for vodka, but had shown himself at supper a passionate admirer of champagne. The ball did not terminate until four in the morning, and the lady, emerging from the mansion, watched curiously the Hetman, whose steps were not quite so steady as they might have been, entering his carriage with the aid of two superb British footmen in plush and powder. The chariot, driven by a bearded Russian coachman, set off at full gallop, and behind it careered a troop of Don Cossacks, whom PLATOFF had brought over with him to England. These fierce but faithful fellows had arrived with the Hetman, at ten o'clock at night; they had quietly tethered their ponies to the railings of the square and had then laid themselves down on the pavement, and uncomplainingly waited six long hours for their chief to make his appearance. Patience, indeed, is one of the chief characteristics of the Cossacks, whether they come from the Don, the Volga, the Ukraine, or the Caucasus. They elect their tribal chiefs, who are sometimes called Atmans, or Hetmans; but since the death of PLATOFF, who passed away very full of fame, fortune, and vodka four years after his visit to England, the heir-presumptive to the crown of All of Russias has always been the Hetman-General of the Cossacks. Their obedience, however, to their Atmans has its limits. Up to a certain point they will implicitly obey the orders given them, and submit to the discipline traditionally observed in their ranks; but they deeply resent any undue interference with their internal concerns by commanding officers of the regular army, and examples are numerous of a whole regiment of Cossacks marking their disapprobation of what they considered wrongly-exerted military authority by suddenly disappearing, lances, whips, horses, and all, in the middle of the night, and betaking themselves to their native steppes, whither it has usually been deemed politic not to pursue them. By degrees the vanished warriors will regret their elopement and become absorbed in fresh corps enrolled in the regions which they inhabit. Altogether, the Cossacks may be considered as in many respects as mysterious a race as the gipsies. They seem to have been born on horseback, and their bravery ever since the days of MAZEPPA, and long before, has been literally handed down from father to son.