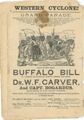

The Wild West Buffalo Bill and Dr. Carver

U.S. Scouts

Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exibition

Hon. Wm. F. Cody. Buffalo Bill

Congress to W. F. Cody. Buffalo Bill Scout & Guide.

Dr. Wm. F. Carver Evil Spirit of the Plain.

Presented to Dr. W. F. Carver Champion Rifle Shot of the United States By His Excellency Rutherford B. Hayes President of the United States of America as a Token of Appreciation of His Skill as a Marksman. 21st April 1879.

This Book was printed by The Calhoun Printing & Engraving 'Co Hartford Conn probably about 1883 —

It was probably a year or two later was this printed = As the first presentation of Cody's Wild West did not occur until May 17 - 1883 when the opening exhibition took place on the Fairground at Omaha Nebraska

per H. H. Gunning

1939

Mr. H. H. Gunning

322 Machen

Toledo, Ohio

Hon. W. F. CODY—"Buffalo Bill,"

Born in 1845

Born in 1845 Died 10th Jan'y 1917 at Denver Colorado

Was born in Scott County, Iowa, from whence his father, Isaac Cody, emigrated a few years afterwards to the distant frontier territory of Kansas, settling near Fort Leavenworth. While still a boy his father was killed in what is now known as the "Border War," and his youth was passed amid all the excitements and turmoil incident to the strife and discord of that unsettled community, where the embers of political contentions smouldered until they burst into the burning flame of civil war. This state of affairs among the white occupants of the territory, and the ingrained ferocity and hostility to encroachment from the native savage, created an atmosphere of adventure well calculated to educate one of his natural temperament to a familiarity with danger and self-reliance in the protective means for its avoidance.

From a child used to shooting and riding, he at an early age became a celebrated pony express rider, then the most dangerous occupation on the plains. He was known as a boy to be most fearless and ready for any mission of danger, and respected by such men then engaged in the express service as Old Jule and the terrible Slade, whose correct finale is truthfully told in Mark Twain's "Roughing It." He accompanied General Albert Sidney Johnston on his Utah expedition, guided trains overland, hunted for a living, and gained his sobriquet by wresting the laurels as a buffalo hunter from all claimants—notably Comstock, in a contest with whom he killed sixty-nine buffalo in one day to Comstock's forty-six—became scout and guide for the now celebrated Fifth Cavalry (of which General E. A. Carr was major), and is thoroughly identified with that regiment's Western history; was chosen by the Kansas Pacific Railroad to supply meat to the laborers while building the road, in one season killing 4,862, besides deer and antelope; and was chief of scouts in the department that protected the building of the Union Pacific. In these various duties his encounters with the red men have been innumerable, and are well authenticated by army officers in every section of the country. In fact wherever you meet an army officer, there you meet an admirer and indorser of Buffalo Bill. He is, in fact, the representative man of the frontiersmen of the past — that is, not the bar-room brawler or bully of the settlements, but a genuine specimen of Western manhood—a child of the plains, who was raised there, and familiar with the country previous to railroads, and when it was known on our maps as the "Great American Desert." By the accident of birth and early association, a man who became insensibly inured to the hardships and dangers of primitive existence and possessed of those qualities that afterward enabled him to hold positions of trust and without his knowing or intending it, made him nationally famous.

Gen. Richard Irving Dodge, Gen. Sherman's chief staff, correctly states in his "Thirty Years Among Our Wild Indians": "The success of every expedition against Indians depends, to a degree, on the skill, fidelity, and intelligence of the men employed as scouts, for not only is the command habitually dependent on them for good routes and comfortable camps, but the officer in command must rely on them almost entirely for their knowledge of the position and movements of the enemy."

Therefore, besides mere personal bravery, a scout must possess the moral qualities associated with a good captain of a ship — full of self-reliance in his own ability to meet and overcome any unlooked-for difficulties, to be a thorough student of nature, a self-taught weather prophet, a geologist by experience, an astronomer by necessity, a naturalist, and thoroughly educated in the warfare, stratagems, trickery, and skill of his implacable Indian foe. Because in handling expeditions or leading troops on him alone depends correctness of destination, avoidance of dangers, protection against sudden storms, the finding of game, grass, woods, and water, the lack of which, of course, is more fatal than the deadly bullet. In fact, more lives have been lost on the plains from incompetent guides than ever the Sioux or Pawnees destroyed.

Our best Indian-fighting officers are quick to recognize these traits in those claiming frontier lore, and to no one in the military history of the West has such deference been shown by them than to W. F. Cody, as is witnessed by the continuous years of service he has passed, the different commands he has served, the expeditions and campaigns he has been identified with, his repeated holding, when he desired, the position of "Chief of Scouts of United States Army," and the intimate associations and contact resulting from it with Gen. W. T. Sherman with whom he was at the making of the Comanche and Kiowa treaty), Gen. Phil. Sheridan (who has often given him special recognition and chosen him to organize expeditious, notably that of the Duke Alexis) old Gen. Harney, Gens. W. S. Hancock, Crook, Pope, Miles, Ord, Augur, Terry, McKenzie, Carr, Forsythe, Merritt, Brisbin, Emory, Gibbon, Royal, Hazen, Duncan, Palmer, Pembroke, and the late-lamented Gen. Custer. His story, in fact, would be almost a history of the middle West and, though younger, equaling in term of service and in personal adventure Kit Carson, Old Jim Bridger, California Joe, Wild Bill, and the rest of his [?]and gone associates.

As another evidence of the confidence placed in his frontiersmanship, it may suffice to mention the celebrities whose money and position most naturally sought the best protection the Western market could afford, and who chose to place their lives in his keeping: Sir George Gore, Earl Dunraven, James Gordon Bennett, Duke Alexis, Gen. Custer, Lawrence Jerome, Remington, Professor Ward of Rochester, Professor Marsh of Yale College, Major J. G. Hecksher, Dr. Kingsley (Canon Kingsley's brother), and others of equal rank and distinction. All books of the plains, his exploits with Carr, Miles, and Crook, published in the New York Herald and Times in the summer 1876, when he killed Yellow Hand in front of the military command in an open-handed fight, are too recent to refer to.

The following letter of his old commander and celebrated Indian fighter, Gen. E. A. Carr, written years ago relative to him, is a tribute as generous as any brave man has ever made to one of his position:

"From his services with my command, steadily in the field, I am qualified to bear testimony as to his qualities and character.

"He was very modest and unassuming. He is a natural gentleman in his manners as well as in character, and has none of the roughness of the typical frontiersman. He can take his own part when required, but I have never heard of his using a knife or a pistol, or engaging in a quarrel where it could be avoided. His personal strength and activity are very great, and his temper and disposition are so good that no one has reason to quarrel with him.

"His eyesight is better than a good field glass; he is the best trailer I ever heard of, and also the best judge of the 'lay of country' — that is, he is able to tell what kind of country is ahead, so as to know how to act. He is a perfect judge of distance, and always ready to tell correctly how many miles it is to water, or to any place, or how many miles have been marched.

* * * *

"Mr. Cody seemed never to tire and was always ready to go, in the darkest night or the worst weather, and usually volunteered, knowing what the emergency required. His trailing, when following Indians or looking for stray animals or game, is simply wonderful. He is a most extraordinary hunter.

"In a fight Mr. Cody is never noisy, obstreperous, or excited. In fact, I never hardly noticed him in a fight, unless I happened to want him, or he had something to report, when he was always in the right place, and his information was always valuable and reliable.

"During the winter of 1866 we encountered hardships and exposure in terrific snow storms, sleet, etc., etc. On one occasion that winter Mr. Cody showed his quality by quietly offering to go with some dispatches to Gen. Sheridan, across a dangerous region, where another principal scout was reluctant to risk himself.

"Mr. Cody has since served with me as post guide and scout at Fort McPherson, where he frequently distinguished himself.

* * * *

"In the summer of 1876 Cody went with me to the Black Hills region, where he killed Yellow Hand. Afterwards he was with the Big Horn and Yellowstone expedition. I consider that his services to the country and the army by trailing, finding, and fighting Indians, and thus protecting the frontier settlers, and by guiding commands over the best and most practicable routes, have been far beyond the compensation he has received."

Thus it will be seen that notwithstanding it may sometimes be thought his fame rests upon the pen of the romancer and novelist, had they never been attracted to him (and they were solely by his sterling worth), W. F. Cody would none the less have been a character in American history. Having assisted in founding substantial peace in Nebraska, where he was honored by being elected to the legislature (while away on a hunt), he has settled at North Platte, to enjoy its fruits and minister to the wants and advancements of the domestic circle with which he is blessed. On the return from Europe of his old prairie friend, Dr. Carver, in rehearsing the old time years agone on the Platte, the Republican, and the Medicine, they concluded to reproduce some of the interesting scenes on the plains and in the "wild West."

The history of such a man, attractive as it already has been to the most distinguished officers and fighters in the United States Army, must prove doubly so to the men, women, and children who have heretofore found only in the novel the hero of rare exploits, on which imagination so loves to dwell. Young, sturdy, a remarkable specimen of manly beauty, with the brain to conceive and nerve to execute, Buffalo Bill par excellence is the exemplar of the strong and unique traits that characterize a true American frontiersman.

AT PEACE.

A full and complete "Life of Buffalo Bill" has been published. The book contains 865 large octavo pages with eighty fine engravings, including superb portrait of the author. Send $1.00 to Frank E. Bliss, Hartford, Conn., who will send the book by mail on receipt of price.

Dr. W. F. CARVER.—The Evil Spirit of the Plains.

CALHOUN PRINT CO. HFD. CT.

W. F. Carver, whose renown as the most expert rifleman in the universe, and whose phenomenal skill is of such superlative excellence that his "form" is, by the shooting fraternity, practical hunters, and military experts of all nations, acknowledged to be the perfect acme of possible merit in its line, was born at Saratoga Springs, N. Y., in 1840. His history eclipses anything yet adduced in the most extravagant romance, covering as it does—and possibly in his case alone of all living men—the extremes that exist between the stolen emigrant boy of the uncivilized Western plains of America, living a captive among the savage red men, to the tribute of this continent of marksmen and the admiring patronage of the crowned occupants and the courts of the palaces of England and continental Europe—a fame so rarely achieved in any profession of art among one's fellow-men that it can only be expressed as universal—excelsior. His father, migrating in 1844 to the then far West, settled near the Falls of St. Anthony, in Minnesota, where now stands the populous city of Minneapolis. A raid of the Teton and Crow Sioux, in a short year afterwards, during the temporary absence of the father, resulted in the butchery of his mother and sister, burning of the settlement, and the captivity of the subject of our sketch. Through some unlooked-for goodness in a chief called Red Wing, whom the little stranger's appearance pleased, the boy's life was spared, and he was adopted and for years remained an accepted member of the tribe. Thrilling as his experiences in Indian life were, and as interesting as they may be, space prevents any lengthy relation of them, though the fact that thirteen years were passed with varying joys and sorrows will suffice to show how eventful it must have been. With all its regrets, however, the years spent in close alliance with primitive man in his nomadic life, outdoor sports, hunting, horsemanship, etc., laid the foundation of that now splendid physique and extraordinary skill that causes his present renown and has gained for him, through his deadly aim, the title of "The Evil Spirit of the Plains."

The death of his patron, Red Wing, absolving him from his debt of gratitude to the tribe, he joined at the first opportunity a trapper named Brewster, and, with the invading hunters, waged a war of unrelenting vengeance against the red devils, killing among others the noted chief Wolf Catcher, and became one of the best riders, sharpest shooters, expert hunters, and one of the most marked celebrities on the plains. Eventually his fame became widespread on the prairie, and falling in with Cody (Buffalo Bill), Omohundro (Texas Jack), Hicock (Wild Bill), and California Joe, they for years rode the plains together, hunting, trapping, and assisting civilization in its progress. Their coming East, and the encroachments of the settlers, caused his attention to be drawn to the possibilities of extending his fame; but, when first challenging the champions of the country and asserting his abilities, his offers were treated with derision and his feats on foot and horse were voted imaginary. Going to California, then sweeping the continent from ocean to ocean, this wizard rifleman convinced all doubters, became the season's wonder, and in his advent marked a new era in the history of American marksmanship. Nor was his skill more remarkable than the wonder of his endurance, he having, with a rifle, beaten the greatest shotgun score on record, by breaking, at Brooklyn, N. Y., July 13, 1878, 5,500 glass balls thrown in the air in 7 hours 36 minutes. During the feat he raised to his shoulder 62,120 pounds, or 31 1/8 tons in weight. In working the lever of the rifle he moved 248,480 pounds with the middle finger of his right hand, and withstood from the recoil an aggregate weight of 298,176 pounds, equal to 149 tons.

Dr Wm. F. Carver

Evil Spirit of the Plains Champion Rifle Shot of the World

His marvelous exhibitions caused his sojourn in England and his visits to Ireland, Wales, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Hungary, and Austria to savor of a continual ovation from the admiring populace and the no less astonished and delighted members of royalty. By special request, he exhibited at Sandringham before the Queen, Prince and Princess of Wales, Duke and Duchess of Connaught, and the members of the royal household, receiving the very exceptional gift of the "Prince of Wales Feathers" and the "Princess of Wales Horseshoe"—an emblem of Denmark—and received the plaudits of 30,000 soldiers who were assembled to witness his feats, under the command of Gen. Sir Robert Steel, at Aldershsot, was personally congratulated and decorated with valuable mementos by the Emperor Wilhelm of Germany, who titled him "Der Shutzen Konig," the Crown Prince and Princess, others of the royal family, Von Bismarck, and the renowned soldier, Von Moltke and his staff, whose special praise was more than enthusiastic. The Grand Duke Albert of Austria, Count Wilzk (with whom he enjoyed a sixteen-days' chamois hunt in the Styrian Mountains), and the King of Saxony also paid tribute to his skill. In fact no visiting scholar, soldier, or statesman that ever left American shores received more consideration in those countries, where the momentary possibilities of war's exigencies lends an absorbing interest in that deadly art, whose complete development is often a motive for desired peace.

Dr. Carver is a fine specimen of physical manhood—six feet two and a half inches in height, and built from "the ground up;" is polished in manner, and of pleasing address; modest in demeanor; with all the accomplishments in flood and field of his Indian tutors; of undaunted nerve; is a pistol and bow and arrow expert, a perfect horseman—in fact, a model plainsman.

Having returned from his European triumphs, he has joined partnership with his old friend, Buffalo Bill, in giving an instructive illustration of "the wild West," which will be enhanced by the marksmanship of this wonder of the border, whose manly merits have caused him to be honored from the PRAIRIE TO THE PALACE.

EXHIBITION OF MARKSMANSHIP

BEFORE

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales,

BY

DR. WM. F. CARVER

CHAMPION RIFLE SHOT OF THE WORLD,

AT

SANDRINGHAM, TUESDAY, APRIL 15th, 1879.

GIVEN BY COMMAND.

Programme.

RIFLE.

-

MOVING OBJECTS.

- 1.—Shooting 75 Glass Balls out of 100.

- 2.—Shooting Glass Ball thrown very high in the air.

- 3.—Shooting Glass Ball thrown across in front of shooter.

- 4.—Shooting a Glass Ball thrown straight at the shooter.

- 5.—Shooting a Falling Ball.

- 6.—Right and left Double Shot.

- 7.—Shooting four shots at a Glass Ball thrown in the air, missing it with the first three shots, loading the Rifle three times while the Ball is in the air, and breaking it with the fourth shot before reaching the ground.

- 8.—Shooting under a Glass Ball placed on the ground, the bullet tearing up the ground and projecting the ball into the air, loading the rifle, and breaking the ball with the second shot before reaching the ground.

- 9.—Shooting Marbles thrown into the air.

- 10.—Shooting a Brick thrown into the air, smashing it in pieces, loading the rifle, and hitting one of the flying pieces before it reaches the ground.

- 11.—Fast shooting with Winchester Rifle; breaking 10 Balls in 20 seconds.

- 12.—Trap shooting—shooting Glass Balls thrown from a trap with Rifle, single bullet.

- 13.—Coin shooting—shooting Pennies thrown into the air.

- 14.—Time shooting—breaking too Glass Balls in five minutes.

-

STATIONARY OBJECTS.

- 15.—Shooting Glass Ball, Rifle upside down on top of shooter's head.

- 16.—Shooting Glass Ball, Rifle turned sideways.

- 17.—Shooting Glass Ball, standing with back to object, sighting by aid of a mirror.

- 18.—Shooting a Glass Ball placed upon the ground, holding the Rifle upon the hip, shooting without sighting.

- 19.—Shooting a Glass Ball, the Rifle upside down, shooter lying upon his back over a stool.

- 20.—Shooting 10 shots at a target in 20 seconds, placing the balls nearly all together.

- 21.—Miscellaneous Shooting.

-

SHOT GUN.

- 22.—Shooting 100 Glass Balls sprung from two traps, right and left.

- 23.—Shooting 50 pair of Glass Balls sprung from one trap.

- 24.—Shooting a Falling Ball.

- 25.—Shooting from right to left shoulder.

- 26.—Shooting Glass Ball sprung from trap, shooter standing with back to trap when sprung, turning, and breaking the ball.

- 27.—Shooting Glass Ball with one hand only.

- 28.—Shooting Glass Ball thrown by shooter.

- 29.—Shooting Glass Balls thrown in any direction by the assistant.

- 30.—The Hip Shot—Shooting Glass Ball sprung from trap, without sighting, holding the gun on the hip.

-

HORSE-BACK SHOOTING.

- Riding his famous horse "Winnemucca," used by him in Buffalo Hunting upon the Western Plains of America.

- 31.—Target shooting with rifle, horse running at full speed.

- 32.—Shooting Glass Ball thrown into the air from horseback, horse running at full speed.

-

ILLUSTRATIONS OF LASSO THROWING.

-

AS PRACTISED UPON THE WESTERN PLAINS.

- 1.—Of catching a man while standing.

- 2.—Of catching a man while walking.

- 3.—Of catching a man while running.

- 4.—Of the Under-throw—Catching man by the foot.

- 5.—Of catching a horse running.

- 6.—Of catching a rider on horseback, running at full speed.

Major FRANK J. NORTH, Chief of Pawnee Scouts.

Frank North, as he is familiarly called upon the prairies, was the first man to enlist Indians in the United States service, he having organized a band of twenty-seven young Pawnee warriors and been made Lieutenant over them.

Major North is a native of New York State, and was born in 1840; but his father removed to Nebraska, settling near Columbus, in the winter of 1856-1857, and directly thereafter was frozen to death at Emigrant Crossing, on Big Pappillion Creek, while trying to secure wood for his suffering family.

Shortly after the death of his father young North joined a party of trappers—McMurray, Glass, and Messenger—and began taking beaver and otter on the tributaries of Platte River; but, meeting with indifferent success, returned to Columbus and engaged in anything that promised remuneration, as the family was almost entirely dependent on him for support.

In 1860, being now twenty years of age, Frank procured employment with Agent DePuy, at the Pawnee Indian Reservation. Here, while performing his other duties, he acquired such a thorough knowledge of the Pawnee language that in the following year he was engaged as interpreter by the Indian Commissioner.

From the breaking out of the Sioux war, in 1864, Major North began to win a name for himself as a man who had no superior for bravery, and whose abilities as a scouting officer were something wonderful, while his management of his Pawnee Indian scouts was perfect, he having them under better discipline and control than their own chiefs could gain over them.

Acting under orders from Gen. Custer, Lieut. North enlisted one hundred more Pawnee warriors, who were then equipped like the regular cavalry, and North was commissioned Captain.

On the 13th of January, 1865, the company was mustered into service, the delay being due to difficulties regarding their acceptance by the Government, but when regularly put on the muster rolls Capt. North began active operations. Learning of depredations being made by the Sioux in the neighborhood of Julesburg, he took forty of his Pawnees and proceeded directly to the scene of trouble. On the route to Julesburg, he was horrified to find the bodies of no less than fourteen white persons, pilgrims on their way to Pike's Peak, mutilated beyond recognition; their scalps torn off, tongues cut out, legs cut open, and bodies full of arrows. Julesburg had also been attacked, and the garrison was on the point of yielding when rescued. North now pushed after the Sioux with all possible speed, and, meeting with twenty-eight of the incarnate devils, he fell upon them with such irresistible force that not a single Sioux in the party escaped his vengeance.

These Indians whom North had thus annihilated were a predatory band from Red Cloud's forces, and had done an inestimable amount of damage through the section they had invaded. Only a few days previous to their disastrous meeting with Capt. North this same party had suddenly attacked Lieut. Collins, with fourteen men, and killed the entire party.

Shortly after this successful sortie, Capt. North was ordered to pursue a body of twelve Cheyennes and punish them for atrocities committed in the neighborhood of Fort Sedgwick. Taking twenty of his Pawnees, he got on the Cheyenne trail, and, after following it about thirty miles, came up with the enemy, whom he found in line of battle. At the first volley, however, the Cheyennes fled, followed hard by Capt. North. In this pursuit the Pawnees were unable to keep up with their captain, as their horses were too badly jaded to endure extra riding. Capt. North, however, was mounted on a superior animal, and, being full of desperate pluck, was determined to kill one Cheyenne as least. Looking back, at length, he saw his men fully a mile behind him, and several of them dismounted. Realizing the danger of his position, he took deliberate aim and fired at the Cheyennes, one of whom tumbled from his pony dead. At this the other Indians turned on the Captain, and he was compelled to flee for his life.

The Indians rode rapidly after him, shooting constantly, until a bullet struck the Captain's horse in the side, rendering him unfit for further travel. Leaping to the ground, Capt. North used his horse for a breastwork, from which he fired until the position had become too dangerous. He then started to run, but after getting several yards he remembered the two holsters on the saddle, each containing a loaded revolver, and he boldly returned for these. With these pistols he fought the Cheyennes nearly half an hour longer, and until relieved by Lieut. Small. This fight, one of the most daring ever made, is still spoken of, and the story frequently told over and over again among Western men, who almost reverence the name of Frank J. North.

In the March following, while acting under the orders of Gen. Augur, Capt. North raised a battalion of two hundred Pawnees, who were divided into four companies and taken to Fort Kearney, where they were equipped for cavalry service. He was then given a Major's commission, and, with his Indian soldiers, guarded construction trains on the Union Pacific Railroad until its completion to Ogden. In this service he was engaged almost constantly with depredating Sioux and Cheyennes, who descended on the construction trains at every opportunity. After the road had reached Utah, large shipments of silver were being made almost weekly, and as this precious metal was brought into stations in large bricks, which, for want of other storage, was usually piled up on and about the platforms to await shipment, Major North's Indians had also to perform the duty of guarding the precious metal.

When the road was completed, Major North retired to a ranch on Dismal River, sixty-five miles north of North Platte, where he went into the cattle raising business. Buffalo Bill, after his first meeting with Major North at Fort McPherson, served with him on several campaigns, and in this service a very warm friendship sprang up between them, which led to the formation of a copartnership in the cattle ranch on Dismal River. The firm of Cody & North is known among cattle men in every part of America; they now have seven thousand head of cattle and four hundred head of horses, and to every one who calls at their ranch there is a hearty, white man's welcome. Major North, aside from his reputation as an Indian fighter and brave man, is a gentleman of the most generous and noble instincts, popular with all classes, and a friend honest and honorable to the end.

THE HUNT OF THE BISON.

The late-lamented "Texas Jack" gave the following laconic, yet realistic description of this exciting sport in Wilkes' Spirit, March 26, 1877:

My old friends, W. F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill") and "Doc." Carver, paid me a visit the other evening, having returned from a successful hunting trip. The camp fire tête à tête reminded me of my first buffalo hunt with Indians. If I don't get like the butcher's calf and "kind o' give out," I'll try and give you an idea of one of the most exciting scenes I ever saw or read of, not excepting my school-boy impression of Andy Jackson's hoo-doo at New Orleans. I thought I had seen fun in a Texas cattle stampede, been astonished in a mustang chase; but it wasn't a marker, and it made me believe that Methuselah was right when he suggested that the oldest could "live and learn." It is a pity the old man didn't stick it out. He could have enjoyed this lesson.

A few years ago I was deputized United States Agent, under Major North, to accompany a party of Pawnee and Ponca Indians. Although "blanket Indians" (living wild), they have for a long time been friends of the Government, and have done excellent service under command of the justly celebrated Major Frank North, whose famed Pawnee scouts (now at Sidney, Neb.) have always been a terror to the Sioux nation. Owing to their hatred of each other, it is necessary to send an agent with them to prevent "picnics," and also to settle disputes with the white hunters. As Major North was in poor health at that time, this delicate task fell to me.

As I don't like to be longwinded, I'll pass over the scenes and incidents of wild Indian camp life, the magnificent sight of a moving village of "nature's children," looking like a long rainbow in the bright colors of their blankets, beads, feathers, war paint, etc., etc., as it would form a full chapter, and skip an eleven-days' march from the the Loup River Reservation to Plum Creek, on the North Platte, where our runners reported.

Early in the evening, as we were about making camp, my old friend, Baptiste, the interpreter, joyfully remarked: "Jack, the blanket is up three times—fun and fresh meat to-morrow."

There was a great powwowing that night, and all the warriors were to turn out for the grand "buffalo surround," leaving the squaws and papooses in the village.

Just before daybreak, there was a general stir and bustle on all sides, giving evidence of the complete preparations making for the coming events. As it was dark, and I busied in arranging my own outfit, thinking of the grand sight soon

to be witnessed, and wondering how I would "pan out" in the view of my "red brothers," I had not noted the manner of their own arrangements in an important particular that I will hereafter allude to.

to be witnessed, and wondering how I would "pan out" in the view of my "red brothers," I had not noted the manner of their own arrangements in an important particular that I will hereafter allude to.

At a given signal all started, and, when the first blue streaks of dawn allowed the moving column to be visible I had time to make an inspection of the strange cavalcade, and note peculiarities. I saw at once placed at a disadvantage the "white brother."

I had started fully equipped — bridle, saddle, lariat, rifle, pistol, belt, etc. —and astride of my pony. They, with as near nothing in garments as Adam and Eve, only breech clout and moccasins, no saddle, no blanket, not even a bridle, only a small mouth rope, light bow and a few arrows in hand — in fact not an ounce of weight more than necessary, and, unlike myself, all scudding along at a marvelous rate, leading their fiery ponies, so as to reserve every energy for the grand event in prospect.

Taking it all in at a glance, your "humble servant," quite abashed, let go all holts and slipped off his critter, feeling that the Broncho looked like a Government pack mule. I at once mentally gave up the intention of paralyzing my light-rigged side pards in the coming contest. As they were all walking, I thought the buffalo were quite near; but what was my surprise, as mile after mile was scored, that I gradually found myself dropping slowly but surely behind, and, so as not to get left, compelled every now and then to mount and lope to the front, there to perceive from the twinkling eyes of friend "Lo" a smile that his otherwise stolid face gave no evidence of. How deep an Indian can think, and it not be surface plain, I believe has never been thoroughly measured. Just imagine this "lick," kept up with apparent ease by them for ten or twelve miles, and you may get a partial idea of your friend Jack's tribulations.

Fortunately, I kept up, but at what an expense of muscle, verging on a complete "funk," you can only appreciate by a similar spin.

About this time a halt was made, and you bet I was mighty glad of it. Suddenly two or three scouts rode up. A hurried council was held, during which the pipe was passed. Everything seemed to be now arranged, and, after a little further advance, again a halt, when, amid great but suppressed excitement, every Indian mounted his now almost frantic steed, each eagerly seeking to edge his way without observation to the front.

About two hundred horses almost abreast in the front line, say one hundred and fifty wedging in half way between formed a half second line, and one hundred struggling for place—a third line; the chiefs in front gesticulating, pantomiming, and, with slashing whips, keeping back the excited mass, whose plunging, panting ponies, as impatient as their masters, fretted, frothed, and foamed—both seemed moulded into one being, with only one thought, one feeling, one ambition, as with flashing eye they waited for the signal, "Go," to let their pent-up feelings speed on to the honors of the chase.

Their prey is in fancied security, now quietly browsing to the windward in a low, open flat, some half a mile wide and two or three mile long, on top of a high divide, concealed from view by risings and breaks. Gradually they approach the knoll, their heads reach the level, the backs of the buffalo are seen, then a full view, when Pi-ta-ne sha-a-du (Old Peter, the head chief) gives the word, drops the blanket, and they are "off."

Whew! wheez! thunder and lightning! Jerome Parks, and Hippodromes! talk of tornadoes, whirlwinds, avalanches, water-spouts, prairie fires, Niagara, Mount Vesuvius (and I have seen them all except old Vesuv.); boil them all together, mix them well, and serve on one plate, and you will have a limited idea of the charge of this "light brigade." They fairly left a hole in the air. With a roar like Niagara, the speed of a whirlwind, like the sweep of a tornado, the rush of a snow-slide, the suddenness of a water-spout, the rumbling of Vesuvius, with the fire of death in their souls, they pounce on their prey, and in an instant, amid a cloud of dust, nothing is visible but a mingled mass of flying arrows, horses' heels, buffalos' tails, Indian heads, half of ponies, half of men, half of buffalo, until one thinks it a dream, or a heavy case of "jim-jams."

I just anchored in astonishment. Where are they? Ah! there is one; there is another, a third, four, five. Over the plains in all directions they go, as the choice meat hunters cut them out, while in a jumbled mass, circling all around is the main body. The clouds of dust gradually rise as if a curtain was lifted, horses stop as buffalos drop, until there is a clear panoramic view of a busy scene, all quiet, everything still (save a few fleet ones in the distance); horses riderless, browsing proudly, conscious of success; the prairie dotted here, there, everywhere with dead bison; and happy, hungry hunters skinning, cutting, slashing the late proud monarch of the plains.

I was so interested in the sight that I came near being left, when fortunately a lucky long-range shot (the only one fired during the day) at a stray heifer saved my reputation. In about two hours every pony was loaded, their packing being quite a study that would need a deserved and lengthy description. It was wonderful.

As I had a heap of walk out, I proposed to ride in, so took a small cut of choice meat—a straight cut—for camp. Every pony was packed down only mine, seeing which "Peter's pappoose" ("the sun chief") invited himself up behind. Talk of gall—an Indian has got more cheek than a Government mule. He laughed at my objections, but as he had loaned me the pony I had to submit. He even directed the gait, and kept up a continual jabbering of "Wisgoots, ugh! de-goinartsonse stak-ees, ugh!" which I afterward learned meant "Hurry up; I am tired, hungry, and dry—how!"

A reproduction, as far as practical, of the method of buffalo hunting, will be a feature of the Cody & Carver's "Wild West," with a herd of bison, real Indians, hunters, and Western ponies.

Dr Wm F. Carver Champion Rifle Shot of the World

CALHOUN PRINT CO. / HARTFORD, CONN.

"The Evil Spirit of the Plains."

The Wild West Buffalo Bill and Dr Carver's Rocky Mountain & Prairie Exhibition

HISTORICAL COACH OF THE DEADWOOD LINE.

The Indians attack on which will be represented in Cody & Carver's "Wild West," and also its rescue by the Scouts and Plainsmen.

A Historical Coach of the Deadwood Line.

The denizens of the Eastern States of the Union are accustomed to regard the West as the region of romance and adventure. And, in truth, its history abounds with thrilling incidents and surprising changes. Every inch of that beautiful country has been won from a cruel and savage foe by danger and conflict. In the terrible wars of the border which marked the early years of the Western settlements, the men signalized themselves by performing prodigies of valor, while the women, in their heroic courage and endurance, afforded a splendid example of devotion and self-sacrifice. The history of the wagon trains and stage coaches that preceded the railway is written all over with blood, and the story of suffering and disaster, often as it has been repeated, is only known in all of its horrid details to the bold frontiersmen, who, as scouts and rangers, penetrated the strongholds of the Indians, and, backed by the gallant men of the army, became the avant couriers of Western civilization and the terror of the red man.

Among the most stirring episodes in the life of the Western pioneer are those connected with the opening of new lines of travel, for it is here, among the trails and canyons, where lurk the desperadoes of both races, that he is brought face to face with danger in its deadliest forms. No better illustration of this fact is furnished than in the history of the famous DEADWOOD COACH, the scarred and weather-beaten veteran of the original "star route" line of stages, established at a time when it was worth a man's life to sit on its box and journey from one end of its destination to the other. The accompanying picture affords an idea of the old relic, and it is because of its many associations with his own life that it has been purchased by "Buffalo Bill" and his partner, Dr. Carver, and added to the attractions of their "GREAT REALISTIC EXHIBITION OF WESTERN NOVELTIES."

It will be observed that it is a heavily-built Concord stage, and is intended for a team of six horses. The body is swung on a pair of heavy leather underbraces, and has the usual thick "perches," "Jacks," and brakes belonging to such a vehicle. It has a large leather "boot" behind, and another at the driver's footboard. The coach was intended to seat twenty-one men—the driver and two men beside him, twelve inside, and the other six on the top. As it now stands, the leather blinds of the window are worn, the paint is faded, and it has a battered and travel-stained aspect that tells the story of hardship and adventure. Its trips began in 1875, when the owners were Messrs. Gilmour, Salisbury & Co. Luke Voorhees is the present manager. The route was between Cheyenne and Deadwood, via Fort Laramie, Rawhide Buttes, Hat or War Bonnet Creek, the place where Buffalo Bill killed the Indian chief "Yellow Hand," July 17, 1876, Cheyenne River, Red Canyon, and Custer. Owing to the long distance and dangers, the drivers were always chosen for their coolness, courage, and skill.

In its first season the dangerous places on the route were Buffalo Gap, Lame Johnny Creek, Red Canyon, and Squaw Gap, all of which were made famous by scenes of slaughter and the deviltry of the banditti. Conspicuous among the latter were "Doc." Middleton, who is now in prison in Nebraska; "Curley" Grimes, who was killed at Hogan's Ranche; "Peg-Legged" Bradley; Bill Price, who was killed on the Cheyenne River; "Dunk" Blackburn, who is now in the Nebraska State Prison, and others of the same class, representing the most fearless of the road agents of the West.

On the occasion of the first attack, the driver, John Slaughter, a son of the present marshal of Cheyenne, was shot to pieces with buckshot. He fell to the ground, and the team ran away, escaping with the passengers and mail, and safely reached Greely's Station. This occurred at White Wood Canyon. Slaughter's body was recovered, brought to Deadwood, and thence carried to Cheyenne, where it is now buried. The old coach here received its "baptism of fire," and during the ensuing summer passed through a variety of similar experiences, being frequently attacked. One of the most terrific of these raids was made by the Sioux Indians, but the assault was successfully repelled, although the two leading horses were killed. Several commercial travelers next suffered from a successful ambush, on which occasion a Mr. Liebman, of Chicago, was killed, and his companion shot through the shoulder.

After this stormy period it was fitted up as a treasure coach, and naturally became an object of renewed interest to the robbers; but, owing to the strong force of what is known as "shotgun messengers" who accompanied the coach, it was a long time before the bandits succeeded in accomplishing their purpose. Among the most prominent of these messengers were Scott Davis, a splendid scout and one of the self-appointed undertakers of many of the lawless characters of the neighborhood; Boone May, one of the best pistol shots in the Rocky Mountain regions, who killed Bill Price in the streets of Deadwood, together with "Curley" Grimes, one of the road agents; Jim May, a worthy brother—a twin in courage if not in birth. Few men have had more desperate encounters than he, and the transgressors of the law have had many an occasion to feel the results of his keen eye and strong arm whenever it has become necessary to face men who are prepared to "die with their boots on." Still another of these border heroes (for such they may be justly termed) is Gail Hill, now the deputy-sheriff of Deadwood, and his frequent companion was Jesse Brown, an old-time Indian fighter, who has a record of incident and adventure that would make a book. These men constituted a sextette of as brave fellows as could be found on the frontier, and their names are all well known in that country.

At last, however, some of them came to grief. The bandits themselves were old fighters. The shrewdness of one party was offset by that of the other, and on an unlucky day the celebrated Cold Spring tragedy occurred. The station had been captured, and the road agents secretly occupied the place. The stage arrived in its usual manner, and, without suspicion of danger, the driver, Gene Barnett, halted at the stable door. An instant afterwards a volley was delivered that killed Hughey Stevenson, sent the buckshot through the body of Gail Hill, and dangerously wounded two others of the guards. The bandits then captured the outfit, amounting to some sixty thousand dollars in gold.

On another occasion the coach was attacked, and, when the driver was killed, saved by a woman—Martha Canary, better known at the present time in the wild history of the frontier as "Calamity Jane." Amid the fire of the attack, she seized the lines, and, whipping up the team, safely brought the coach to her destination.

When Buffalo Bill returned from his scout with Gen. Crook, in 1876, he rode in this self-same stage, bringing with him the scalps of several of the Indians whom he had met. When afterwards he learned that it had been attacked and abandoned and was lying neglected on the plains, he organized a party, and, starting on the trail, rescued and brought the vehicle into camp.

With the sentiment that attaches to a man whose life has been identified with the excitement of the far West, the scout has now secured the coach from Col. Voorhees, the manager of the Black Hills stage line, and hereafter it will play a different rôle in its history from that of inviting murder and being the tomb of its passengers. And yet the "Deadwood Coach" will play no small part in the entertainment that has been organized by Buffalo Bill and Dr. Carver for the purpose of representing some of the most startling realities of Western life, in a vivid representation of one of the Indian and road agents' combined attacks.

Terrors of a Stampede.

The Cow Boys.

Among the many features of "the wild West," not the least attractive will be the advent in the East of a band of veritable "cow-boys," a class without whose aid the great grazing Pampas of the West would be valueless, and the Eastern necessities of the table, the tan-yard, and the factory would be meagre. These will be the genuine cattle herders of a reputable trade, and not the later misnomers of "the road," who, in assuming an honored title, have tarnished it in the East, while being in fact the cow-boys' greatest foe, the thieving, criminal "rustler." To Wilkes' Spirit, of March, the editor is indebted for a just tribute and description of the American ranchman.

THE COW-BOY.

"The cow-boy! How often spoken of, how falsely imagined, how greatly despised (where not known), how little understood! I've been there considerable. How sneeringly referred to, and how little appreciated, although his title has been gained by the possession of many of the noblest qualities that form the romantic hero of the poet, novelist, and historian: the plainsman and the scout. What a school it has been for the latter? As "tall oaks from little acorns grow," the cow-boy serves a purpose, and often develops into the most celebrated ranchman, guide, cattle king, Indian fighter, and dashing ranger. How old Sam Houston loved them, how the Mexicans hated them, how Davy Crockett admired them, how the Comanches feared them, and how much you "beef-eaters" of the rest of the country owe to them, is a large-sized conundrum. Composed of many "to the manner born," but recruited largely from Eastern young men, they were taught at school to admire the deceased little Georgie in exploring adventures, and, though not equaling him in the "cherry-tree goodness," were more disposed to kick against the buldozing of teachers, parents, and guardians.

As the rebellious kid of old times filled a handkerchief (always a handkerchief, I believe) with his all, and followed the trail of his idol, Columbus, and became a sailor bold, the more ambitious and adventurous youngster of later days freezes on to a double-barreled pistol, and steers for the bald

Calhoun Print, Hartford, Conn.The Wild West Indian Races

Now, "cow sense" in Texas implies a thorough knowledge of the business, and a natural instinct to divine every thought, trick, intention, want, habit, or desire of his drove, under any and all circumstances. A man might be brought up in the States swinging to a cow's tail, yet, taken to Texas, would be as useless as a last year's bird's nest with the bottom punched out. The boys grow old soon, and the old cattle-men seem to grow young; thus it is that the name is applied to all who follow the trade. The boys are divided into range-workers and branders, road-drivers and herders, trail-guides and bosses.

As the railroads have now put an end to the old-time trips, I will have to go back a few years to give a proper estimate of the duties and dangers, delights and joys, trials and troubles, when off the ranch. The ranch itself and the cattle trade in the State still flourish in their old-time glory, but are being slowly encroached upon by the modern improvements that will, in course of time, wipe out the necessity of his day, the typical subject of my sketch. Before being counted in and fully endorsed, the candidate has had to become an expert horseman, and test the many eccentricities of the stubborn mustang; enjoy the beauties, learn to catch, throw, fondle—oh! yes, gently fondle (but not from behind)—and ride the "docile" little Spanish-American plug, an amusing experience in itself, in which you are taught all the mysteries of rear and tear, stop and drop, lay and roll, kick and bite, on and off, under and over, heads and tails, hand-springs, triple somersaults, standing on your head, diving, flip-flaps, getting left (horse leaving you fifteen miles from camp—Indians in the neighborhood, etc.), and all the funny business included in the familiar term of "bucking," then learn to handle a rope, catch a calf, stop a crazy cow, throw a beef steer, play with a wild bull, lasso an untamed mustang, and daily endure the dangers of a Spanish matador, with a little Indian scrape thrown in, and if there is anything left of you they'll christen it a first-class cow boy. Now his troubles begin (I have been worn to a frizzled end many a time before I began); but after this he will learn to enjoy them—after they are over.

As the general trade on the range has often been described, I'd simply refer to a few incidents of a trip over the plains to the cattle markets of the North, through the wild and unsettled portions of the Territories, varying in distance from fifteen hundred to two thousand miles—time, three to six months—extending through the Indian Territory and Kansas to Nebraska, Colorado, Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, and sometimes as far as California. Immense herds, as high as thirty thousand or more in number, are moved by single owners, but are driven in bands of one to three thousand, which, when under way, are designated "herds." Each of these have from ten to fifteen men, with a wagon driver and cook, and the "king pin of the outfit," the boss, with a supply of two or three ponies to a man, an ox team, and blankets; also jerked beef and corn meal—the staple food. They are also furnished with mavericks or "doubtless-owned" yearlings for the fresh meat supply. After getting fully under way, and the cattle broke in,

from ten to fifteen miles a day is the average, and everything is plain sailing, in fair weather. As night comes on, the cattle are rounded up in small compass, and held until they lie down, when two men are left on watch, riding round and round them in opposite directions, singing or whistling all the time for two hours, that being the length of each watch. This singing is absolutely necessary, as it seems to soothe the fears of the cattle, scares away the wolves or other varmints that may be prowling around, and prevents them from hearing any other accidental sound, or dreaming of their old homes, and if stopped would, in all probability, be the signal for a general stampede. "Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast," if a cow-boy's compulsory bawling out lines of his own composition,

Lay nicely now, cattle, don't heed any rattle,

But quietly rest until morn;

For if you skedaddle, we'll jump in the saddle,

And head you as sure as you're born,

can be considered such.

from ten to fifteen miles a day is the average, and everything is plain sailing, in fair weather. As night comes on, the cattle are rounded up in small compass, and held until they lie down, when two men are left on watch, riding round and round them in opposite directions, singing or whistling all the time for two hours, that being the length of each watch. This singing is absolutely necessary, as it seems to soothe the fears of the cattle, scares away the wolves or other varmints that may be prowling around, and prevents them from hearing any other accidental sound, or dreaming of their old homes, and if stopped would, in all probability, be the signal for a general stampede. "Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast," if a cow-boy's compulsory bawling out lines of his own composition,

Lay nicely now, cattle, don't heed any rattle,

But quietly rest until morn;

For if you skedaddle, we'll jump in the saddle,

And head you as sure as you're born,

can be considered such.

But on nights when "Old Prob." goes on a spree, leaves the bung out of his water barrel above, prowls around with his flash box, raising a breeze whispering in tones of thunder, and the cow-boy's voice, like the rest of the outfit, is drowned out, steer clear, and prepare for action. If them quadrupeds don't go insane, turn tail to the storm, and strike out for civil and religious liberty, then I don't know what "strike out" means. Ordinarily so clumsy and stupid-looking, a thousand beef steers can rise like a flock of quail on the roof of an exploding powder mill, and will scud away like a tumble weed before a high wind, with a noise like a receding earthquake. Then comes fun and frolic for the boys!

Talk of "Sheridan's ride, twenty miles away!" That was in the daytime, but this is the cow-boy's ride with Texas five hundred miles away, and them steers steering straight for home; night time, darker than the word means, hog wallows, prairie dog, wolf, and badger holes, ravines and precipices ahead, and, if you do your duty, three thousand stampeding steers behind. If your horse don't swap ends, and you hang to them till daylight, you can bless your lucky stars. Many have passed in their checks at this game. The remembrance of the few that were foot loose in the Bowery a few years ago will give an approximate idea of three thousand raving bovines on the warpath. As they tear through the storm at one flash of lightning, they look all tails, and at the next flash all horns. If Napoleon had a herd at Sedan, headed in the right direction, he would have driven old Billy across the Rhine.

The next great trouble is in crossing streams, which are invariably high in the driving season. When cattle strike swimming water they generally try to turn back, which eventuates in their "milling," that is, swimming in a circle, and, if allowed to continue, would result in the drowning of many. There the daring herder must leave his pony, doff his toggs, scramble over their banks and horns to scatter them, and, with whoops end yells, splashing, dashing, and didoes in the water, scare them to the opposite bank. This is not always done in a moment, for a steer is no fool of a swimmer; I have seen one hold his own for six hours in the Gulf after having jumped overboard. As some of the streams are very rapid, and a quarter to half a mile wide, considerable drifting is done. Then the naked herder has plenty of amusement in the hot sun, fighting green head flies and mosquitoes, and peeping around for Indians, until the rest of the lay-out is put over—not an easy job. A temporary boat has to be made of the wagon box, by tacking the canvas cover over the bottom, with which the ammunition and grub it ferried across, and the running gear and ponies are swam over afterwards. Indian fights and horse thief troubles are part of the regular rations. Mixing with other herds and cutting them out, again avoiding too much water at times, and hunting for a drop at others, belongs to the regular routine.

Buffalo chips for wood a great portion of the way (poor substitute in wet weather), and the avoiding of prairie fires later on, varies the monotony. In fact, it would fill a book to give a detailed account of a single trip, and it is no wonder the boys are hilarious when it ends, and, like the old toper, "swears no more for me," only to return and go through the mill again.

How many, though, never finish, but mark the trail with that silent graves! no one can tell. But when Gabriel toots his horn, the "Chisholm trail" will swarm with cow-boys. "Howsomever, we'll all be thar," let's hope, for a happy trip, when we say to this planet, adios!

J. B. Omohundro (Texas Jack).Among the leading celebrities in the present party will be the renowned BUCK TAYLOR, a man whose great strength, nerve, endurance, and skill is historical in the West; JIM LAWSON, equally distinguished as a lassoist and roper; Bud Ayers, Dick Bean, and others, who will appear in feats of horsemanship, riding bucking mustangs, roping cattle, throwing buffalo, etc., eclipsing in agility and danger the Spanish matadors of old.

Mexicans

The Vaquero of the Southwest.

Between the "cow-boy" and the "vaquero" there is only a slight line of demarcation. The one is usually an American inured from boyhood to the excitements and hardships of his life, and the other represents in his blood the stock of the Mexican, or it may be of the half-breed.

In their work, the methods of the two are similar; and, to a certain extent, the same is true of their associations. Your genuine vaquero, however, is generally, when off duty, more of a dandy in the style and get-up of his attire then his careless and impetuous compeer. He is fond of gaudy clothes, and when you see him riding well mounted into a frontier town, the first thought of an Eastern man is that a circus has broken loose in the neighborhood, and this is one of the performers. The familiar broad-brimmed sombrero covers his head; a rich jacket, embroidered by his sweetheart perhaps, envelopes his shapely shoulders; a sash of blue or red silk is wrapped around his waist, from which protrude a pair of revolvers; and buckskin trowsers, slit from the knee to the foot and ornamented with rows of brass or silver buttons, complete his attire, save that enormous spurs, with jingling pendants, are fastened to the boots, and announce in no uncertain sound the presence of the beau-ideal vaquero in full dress.

His saddle is of the pure Mexican type, with high pommel, whereon hangs the inevitable lariat, which in his hands is almost as certain as a rifle shot.

Ordinarily he is a peaceful young fellow, but when the whisky is present in undue proportions he is a good individual to avoid. Like the cow-boy, he is brave, nimble, careless of own life, and reckless, when session requires, of those of other people. At heart he is not bad. The dependence on himself which his calling demands, the dangers to which he is subjected while on duty, all compel a sturdy self-reliance, and he is not slow in exhibiting the fact that he possesses it in a sufficient degree at least for his own protection. True types of this peculiar class, seen nowhere else than on the plains, will be among the attractions of the show; and the men will illustrate the methods of their lives in connection with the pursuit and catching of animals, together with the superb horsemanship that is characteristic of their training.

The Wild Equine Rover of the Plains, and his Captor.

Shakespeare on the Horse.

IN "VENUS AND ADONIS."

Imperiously he leaps, he neighs, he bounds, And now his woven girths he breaks asunder; The bearing earth with his hard hoof he wounds, Whose hollow womb resounds like heaven's thunder; The iron bit he crushes 'tween his teeth, Controlling what he was controlled with. His ears up-pricked, his braided hanging mane Upon his compassed crest now stand on end; His nostrils drink the air, and forth again As from a furnace, vapors doth he send; His eye, which scornfully glisters like fire, Shows his hot courage and his high desire. Sometimes he trots, as if he told the steps With gentle majesty and modest pride; Anon he rears upright, curvets, and leaps, As who should say, Lo thus my strength is tried; And this I do to captivate the eye Of the fair breeder that is standing by. What recketh he his rider's angry stir, His flattering holla, or his "Stand, I say"? What cares he now for curb of pricking spur, For rich caparisons, or trapping gay? He sees his love, and nothing else he sees, Nor nothing else with his proud sight agrees. Look, when a painter would surpass the life In limning out a well-proportioned steed, His art with nature's workmanship at strife, As if the dead the living should exceed; So did this horse exceed a common one, In shape, in color, courage, pace, and bone. Round hoof'd, short jointed, fetlocks shag and long. Broad breast, full eye, small head, and nostrils wide, High crest, short ears, straight legs, and passing strong. Thin mane, thick tail, broad buttock, tender hide. Look, what a horse should have he did not lack, Save a proud rider on so proud a back.

Dead, but not Forgotten.

Jack Crawford, familiarly known as "Captain Jack, the Poet Scout of the Black Hills," wrote the following lines, just after the "Custer Massacre," upon receiving the following dispatch from Buffalo Bill: "Jack, old boy, have you heard of the death of Custer?"

GEN. CUSTER.

TEXAS JACK—J. B. OMOHUNDRO.

WILD BILL—JAS. B. HICKOCK.

CUSTER'S DEATH.

Did I hear the news from Custer? Well, I reckon I did, old pard; It came like a streak of lightnin', And, you bet, it hit me hard. I ain't no hand to blubber, And the briny ain't run for years; But chalk me down for a lubber, If I didn't shed regular tears. What for? Now look you here, Bill, You're a bully boy, that's true; As good as e'er wore buckskin, Or fought with the boys in blue; But I'll bet my bottom dollar Ye had no trouble to muster A tear, or perhaps a hundred, At the news of the death of Custer. He always thought well of you, pard, And had it been heaven's will In a few days more you'd met him, And he'd welcome his old scout Bill. For, if ye remember, at Hat Creek, I met ye with General Carr; We talked of the brave young Custer, And recounted his deeds of war. But little we knew even then, pard, (And that's just two weeks ago), How little we dreamed of disaster, Or that he had met the foe— That the fearless, reckless hero, So loved by the whole frontier, Had died on the field of battle In this our centennial year. I served with him in the army, In the darkest days of the war; And I reckon ye know his record, For he was our guiding star; And the boys who gathered round him To charge in the early morn, War just like the brave who perished With him on the Little Horn. And where is the satisfaction, And how will the boys get square? By giving the reds more rifles? Invite them to take more hair? "We want no scouts, no trappers, Nor men who know the frontier;" Phil., old boy, you're mistaken, We must have the volunteer. Never mind that two hundred thousand, But give us a hundred instead; Send five thousand men towards Reno, And soon we won't leave a red. It will save Uncle Sam lots of money; In fortress we need not invest; Jest wollup the devils this summer, And the miners will do all the rest. The Black Hills are filled with miners, The Big Horn will soon be as full, And which will show the most danger To Crazy Horse and old Sitting Bull— A band of ten thousand frontier men, Or a couple of forts with a few Of the boys in the East now enlisting? Friend Cody, I leave it with you. They talk of peace with these demons By feeding and clothing them well; I'd as soon think an angel from Heaven Would reign with contentment in H-l. And one day the Quakers will answer Before the great Judge of us all, For the death of daring young Custer And the boys who round him did fall. Perhaps I am judging them harshly, But I mean what I'm telling ye, pard; I'm letting them down mighty easy, Perhaps they may think it is hard. But I tell you the day is approaching— The boys are beginning to muster— That day of the great retribution, The day of revenge for our Custer. And I will be with you, friend Cody, My weight will go in with the boys; I shared all their hardships last winter, I shared all their sorrows and joys. Tell them I'm coming, friend William; I trust I will meet you ere long. Regards to the boys in the mountains; Yours, ever; in friendship still strong.On the 17th of July, 1876, at Hat or War Bonnet Creek, W. F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill ") fought and killed the Cheyenne Chief, Yellow Hand, in a single-handed encounter, in front of Gen. Wesley Merritt, Gen. E. A. Carr, the Fifth United States Cavalry, and the chief's band of 800 warriors, and thus scored the first scalp for Custer.

On the 17th of July, —1876—

DEATH OF YELLOW HAND — CODY'S FIRST SCALP FOR CUSTER.

The Bow and Arrow.

The bow is the natural weapon of the wild tribes of the West. Previous to the introduction of firearms it was the

weapon supreme of every savage's outfit, in fact his principal

The Pawnees Astonished.

W. F. Cody, although having established his right to the title of "Buffalo Bill" for years before, had not had opportunity to convince the Pawnees of the justice of the claim previous to the time of the following incident. A short while previously a band of marauding red skin renegades from that nation, while on a stealing excursion near Ellsworth, had occasion to regret their temerity and cause to remember him to the extent of three killed, which fact for a time resulted in an enmity that needed something out of the usual run to establish him in their favor. While on a military expedition under Gen. E. A. Carr upon the Republican he met Major North and the Pawnee scouts. One day a herd of buffalo were descried, and Cody desired to join in the hunt. The Indians objected, telling the Major "the white talker would only scare them away." Seventy-three Indians attacked the herd and killed twenty-three. Later in the day another herd were discovered, and Major North insisted that the white chief have a chance to prove his skill. After much grumbling, they acquiesced grudgingly, and with ill-concealed smiles of derision consented to be spectators. Judge of their surprise, when Cody charged the herd, and single-handed and alone fairly amazed them by killing forty-eight buffalo in thirty minutes, thus forever gaining their admiration and a firm friendship that has since often accrued to his benefit.

Colonel Royal's Wagons.

Once upon the South Fork of the Solomon, Col. Royal ordered Cody to kill some buffalo that were in sight to feed his men, but declined to send his wagons until assured of the game. Bill rounded the herd, and, getting them in a line for camp, drove them in and killed seven near headquarters; or, as the colonel afterwards laughingly remarked, "furnishing grub and his own transportation."

Chasing Meat into Camp.

An Indian's Religion.

The Indian is as religious as the most devout Christian, and lays as much stress on form as a Ritualist. He believes in two Gods, equals in wisdom and power.

One is the Good God. His function is to aid the Indian in all his undertakings, to heap benefits upon him, to deliver his enemy into his hands, to protect him from danger, pain, privation. He directs the successful bullet, whether against an enemy or against the "beasts of the field." He provides all the good and pleasurable things in life. Warmth, food, joy, success in love, distinction in war, all come from him.

The other is the Bad God. He is always the enemy of each individual red man, and exerts to the utmost all his powers of harm against him. From him proceed all the disasters, misfortunes, privations, and discomforts of life. All pain, suffering, cold, disease, the deadly bullet, defeat, wounds, and death.

The action of these two Gods is not in any way influenced by questions of abstract right or morality as we understand them.

"Medicine"—Mystery Man.

Every thwarted thought or desire is attributed to the influence of the Bad God.

He believes not an hour passes without a struggle between these two Gods on his personal account.

The Indian firmly believes in immortality, and life after death, but the power of these Gods does not extend to it. They influence only in this life, and the Indian's condition after death does not depend either on his own conduct while living, or on the will of either of the Gods.

All peccadilloes and crimes bring, or do not bring, their punishment in this world, and whatever their character in life, the souls of all Indians reach, unless debarred by accident, a paradise called by them "The Happy Hunting Grounds."

There are two ways in which an Indian's soul can be prevented from reaching this paradise. One method is by strangulation. The Indian believes the soul escapes from the body by the mouth, which opens of itself at the moment of dissolution to allow a free passage. In case of strangulation, either by design or even accident, the soul can never escape, but remains with or hovering near the remains, even after complete decomposition.

As the soul is always conscious of its isolation and its exclusion from the joys of paradise, this death has peculiar terrors, and he infinitely prefers to suffer at the stake, with all the tortures that ingenuity can devise, than die by hanging.

The other eternal disaster is by scalping the head of the dead body. This is annihilation; the soul ceases to exist. This accounts for the eagerness of Indians to scalp all their enemies, and the care they take to avoid being scalped themselves. Not unfrequently Indians do not scalp slain enemies, believing that each person killed by them, not scalped, will be their servant in the next world. It will be found invariably that the slain foe were either very cowardly or very brave. The first he reserves to be his servant, because he will have no trouble in managing him, and the last to gratify his vanity in the future state by having a servant well known as a renowned warrior in this world.

This superstition is the occasion for the display of the most heroic traits of Indian character. Reckless charges are made and desperate chances taken to carry off unscalped the body of a loved chief, a relative, or friend. Numerous instances have occurred where many were killed in vain efforts to recover and carry off unscalped the bodies of slain warriors. Let the scalp be torn off and the body becomes mere carrion, not even worthy of burial. A Homer might find many an Indian hero as worthy of immortal fame as Achilles for his efforts to save the body of his friend, and no Christian missionary ever evinced a more noble indifference to danger, than the savage Indian displays in his efforts to save his friend's soul and ensure him a transit to the "Happy Hunting Grounds."—Col. Dodge in Our Wild Indians.

Buffalo Bill

Congress to W. F. Cody

Buffalo Bill

Scout & Guide

Diamond Pin

Presented to Buffalo Bill by Duke Alexis

Buffalo Head Diamond Eyes

Presented to Buffalo Bill by Sir George Watts-Garland

CALHOUN PRINT CO.

HARTFORD CONN

The Elk.

This animal is the largest of the genus Ruminantia, being higher at the shoulders than any horse. Its horns weigh sometimes over fifty pounds; accordingly, to bear this heavy weight, its neck is short and strong, taking away much of the elegance of proportion so generally predominant in the deer. But when it is asserted that the elk lacks beauty or majesty, the statement must be made by one who has never seen an elk except stuffed in some museum. But when you see him in all his glory, with full-grown horns, amid the scenery of his own wilderness, no animal ever could be more grand or imposing. The aggregate of his appearance could produce no other effect. In America it resides between the forty-fourth and forty-third degrees, round the Great Lakes, and over the whole of Canada and New Brunswick. The largest elk ever killed in this country was shot by Buffalo Bill, the horns weighing over seventy pounds (one of the heaviest ever known), and were presented by him to the New York Lodge of Elks. A band of these noble animals will form a feature in Cody & Carver's "Wild West."

The Buffalo.

The Buffalo is the true bison of the ancients. It is distinguished by an elevated stature, measuring six to seven feet at the shoulders and ten to twelve feet from nose to tail. Many there are under the impression that the buffalo was never an inhabitant of any country save ours. Their bones have been discovered in the superficial strata of temperate Europe; they were common in Germany in the eighth century. Primitive man in America found this animal his principal means of subsistence, while to pioneers, hunters, emigrants, settlers, and railroad builders this fast-disappearing monarch of the plains was invaluable. Messrs. Cody & Carver have a herd of healthy specimens of this hardy bovine in connection with their instructive exhibition, "The Wild West."

Cody's Corral; or, the Scouts and the Sioux.

A mount-inclosed valley, close sprinkled with fair flowers, As if a shattered rainbow had fallen there in showers; Bright-plumaged birds were warbling their songs among the trees, Or fluttering their tiny wings in the cooling Western breeze. The cottonwoods, by mountain's base, on every side high tower, And the dreamy haze in silence marks the sleepy noontide hour. East, south, and north, to meet the clouds the lofty mounts arise, Guarding this little valley — a wild Western Paradise. Pure and untrampled as it looks, this lovely flower-strewn sod— One scarce would think that e'er, by man, had such a sward been trod. But yonder, see those wild mustangs by lariat held in check, Tearing up the fairest flora, which fairies might bedeck; And, near a camp fire's smoke, we see men standing all around — 'Tis strange, for from them has not come a single word or sound. Standing by cottonwood, with arms close folded on his breast, Gazing with his eagle eyes up to the mountain's crest, Tall and commanding is his form, and graceful is his mien; As fair in face, as noble, has seldom here been seen. A score or more of frontiersmen recline upon the ground, But starting soon upon their feet, by sudden snort and bound! A horse has sure been frightened by strange scent on the breeze, And glances now by all are cast beneath the towering trees. A quiet sign their leader gives, and mustangs now are brought; And, by swift-circling lasso, a loose one fast is caught. Then thundering round the mountain's dark adamantine side, A hundred hideous, painted, and fierce Sioux warriors ride; While, from their throats, the well-known and horrible death-knell, The wild, blood-curdling war-whoop, and the fierce and fiendish yell Strikes the ears of all, now ready to fight, and e'en to die, In that mount-inclosed valley, beneath that blood-red sky! Now rings throughout the open, on all sides clear and shrill, The dreaded battle-cry of him whom men call Buffalo Bill! On, like a whirlwind, then they dash — the brave scouts of the plains Their rifle barrels soft caressed by mustangs' flying manes! On, like an avalanche, they sweep through the tall prairie grass; Down, fast upon them, swooping, the dread and savage mass; Wild yells of fierce bravado come, and taunts of deep despair; While, through the battle-smoke, there flaunts each feathered tuft of hair. And loudly rings the war-cry of fearless Buffalo Bill; And loudly ring the savage yells, which make the blood run chill! The gurgling death-cry mingles with the mustang's schrillest scream, And sound of dull and sodden falls, and bow e's brightest gleam. At length there slowly rises the smoke from heaps of slain, Whose wild war-cries will nevermore ring on the air again. Then, panting and bespattered from the showers of foam and blood, The scouts have once more halted 'neath the shady cottonwood. In haste they are reloading, and preparing for a sally, While the scattered foe, now desperate, are yelling in the valley. Again are heard revolvers, with their rattling, sharp report; Again the scouts are seen to charge down on that wild cohort. Sioux fall around, like dead reeds when fiercest northers blow, And rapid sink in death before their hated pale-face foe! Sad, smothered now is music from the mountain's rippling rill, But wild hurrahs instead are heard from our brave Buffalo Bill, Who, through the thickest carnage, charged over in the van, And cheered faint hearts around him, since first the fight began! Deeply demoralized, the Sioux fly fast with bated breath, And glances cast of terror along that vale of death; While the victors quick dismounted, and looking all around, On their dead and mangled enemies, whose corses strewed the ground. "I had sworn I would avenge them" — were the words of Buffalo Bill— "The mothers and their infants they slew at Medicine Hill. Our work is done—done nobly —I looked for that from you; Boys, when a cause is just, you need but to stand firm and true!"—Beadle's Weekly.A stirring life picture of a battle between the whites and Indians, showing the tactics and mode of warfare of each, will be given by the skilled members of both races in Cody & Carver's representation of scenes in "The Wild West."

Dr. Carver's Wonderful Success.

1883

The Wild West

Indian Encampment

Bucking

Mexicans

cowboys

Pony Express

Scenes in Cody and Carver's Exhibition.

The world renowned marksman, Dr. William G. Carver, has just completed one of the most extraordinary shooting matches with his far famed rival Captain Bogardus, that has ever been witnessed in the world. Two of the greatest shots in the world have in twenty-five matches in the large cities of the United States, within little more than a month, shown admiring thousands what could be done in the way of almost unerring markmanship. The tug of war between the great rivals had to be fought out in order to give the palm of supremacy to the one or the other. Captain Bogardus had achieved a marvelous reputation, and while his name was a household word among marksmen, there was also another who had been familiar with firearms from infancy, and whose skill had been witnessed by the crowned heads of Europe.

In his own country he had given such exhibitions with the rifle and shotgun that he had well earned the title that had been bestowed upon him by the red men of the western forest and prairie, namely, that of the "Evil Spirit." His skill would seem to be almost a supernatural gift; with such ease and dexterity does he poise the gun, and in obedience to the pull of his finger the tiny clay pigeon is shivered into fragments. The following record of the shooting matches in the principal cities of the United States, between the two great marksmen, will show such skill in shooting as has not been and may not again be seen in the nineteenth century. Each of the marksmen made the following shots out of a possible hundred during the recent tournament:

| Carver. | Bogardus. | |

| Chicago, | 72 | 63 |

| St. Louis, | 85 | 69 |

| Cincinnati, | 89 | 74 |

| Kansas City, | 91 | 69 |

| St. Joseph, | 92 | 63 |

| Leavenworth, | 85 | 63 |

| Omaha, | 94 | 90 |

| Council Bluffs, | 96 | 96 |

| Des Moines, | 100 | 97 |

| Davenport, | 95 | 89 |

| Burlington, Ia., | 99 | 99 |

| Quincy, Ill., | 100 | 92 |

| Peoria, | 98 | 92 |

| Terra Haute, | 99 | 95 |

| Indianapolis, | 98 | 97 |

| Dayton, O., | 94 | 94 |

| Columbus, | 76 | 93 |

| Pittsburgh. | 94 | 95 |

| Philadelphia, | 96 | 95 |