German | English

Meitzener Tageblatt

Meitzen, June 3rd/90

[1]

Buffalo Bills Wild West in Dresden.

Von der Grunaer Straße bis zur Prairie des Wilden Westens ist gegenwärtig nur ein Schritt, Wildniß und Cultur sind bloß durch eine Planke getrennt, über welche uns aber der Culturträger, „Geld“ genannt, leicht hinwegsetzt. Mit Befremden nehmen wir indeß jenseit der Verplankung wahr, daß die Wildniß schon sehr civilisirt ist. Deutsche Brauer und amerikanische Conditoren reichen sich hier brüderlich die Hand, die Zelte der Cowboys (Kuhhirten) könnten aus einem deutschen Militärmagazin stammen und selbst den spitzen mit kindlichen Malereien geschmückten Wigwams der Indianer ist eine der neuesten Errungenschaften der Cultur, die Jute, nicht mehr fremd. Es ist ein offenbarer Mangel des Wild–West–Unternehmens, daß man die äußere Ausstattung des Indianerlagers nicht interessanter gestaltet hat. Ganz abgesehen von schönen Scalps und anderen Pelzen hätte man doch eine reiche Sammlung altindianischer Waffen zusammenbringen und eine Ausstellung von Erzeugnissen der Indianer veranstalten können, wie dies mutatis mutandis von den Ausstellern der Singhalesen geschehen ist. Die Indianerinnen liefern hübsche Töpfereien, Feder–und Perlstickereien und sind als Teppichweberinnen in Amerika sehr geschätzt. Von alledem ist im Wilden Westen nichts zu finden und es fehlt daher die Stimmung, welche auf die Indianerscenen wirksam vorbereitete. Dieselben finden in der inneren Verplankung statt, in einer riesigen Arena, welche mindestens 4—5000 Zuschauer faßt und ein ganz respectables Stück Prairie umgiebt. Auch diese ist schon von der Cultur beleckt, und darin sogar mancher sächsischen Stadt weit überlegen, denn vor Beginn der Vorstellung wird sie gründlich besprengt! Am Eingang spielt eine Musikbande in der Tracht der Cowboys, in der Mitte befindet sich eine etwas problematische Coulisse, die muthmaßlich ein Blockhaus darstellen soll, den Hintergrund schließt ein riesiger grüner Vorhang ab. Dieser theilt sich plötzlich und mit wildem gellendem Geheul braust zuerst ein buntes Fähnlein von Arrophus–Indianern, dann eine Rotte Kuhhirten, darauf wieder Indianer, wieder eine Schaar Cowboys u. s. f. herein, welche in rasendem Galopp vor dem ersten Rang abschwenken und hier in Linien hinter einander aufreiten. Die Indianer sind ebenso bunt als die Kuhhirten farblos gekleidet, oder richtiger costümirt, denn ein Theil der Ersteren ist barfuß bis zur Hüfte und von da ab wieder bis an den Hals hinauf; man kann doch wohl einen gelben und rothen Anstrich nicht unter die Kleidungsstücke rechnen. Einige hervorragende Herren ergänzen allerdings dieses Nationalcostüm durch prächtigen, am Kopfe befestigten Federschmuck. Unter den Heransprengenden befinden sich auch vier junge Hinterwäldler–Damen, zierliche Erscheinungen, von denen die eine in den echten Stoff des Wilden Westens, in Hirschleder, gekleidet ist, während die übrigen civilisirte Reitcostüme tragen. Auch Buck Taylor, „der König der Kuhhirten,“ ein prächtiger baumlanger Reiter mit langem Haarschopf der Scalplocke, ist einfach gekleidet, der Held des Tages aber, Büffel–Wilhelm, trägt ein phantastisches, mit Seide gesticktes Ledercoller und reitet einen sehnigen, ziemlich eleganten Schimmel mit einer Leichtigkeit und Eleganz, wie wir sie noch in keinem Cirkus gesehen haben. Er ist der Indianer–Romanheld, wie er im Buche steht, ein nicht mehr junger, aber noch ungebeugter bildschöner Recke voll angeborner Anmuth, wenngleich nicht ohne theatralische Affectation, der im wahren Sinne des Wortes mit dem Pferde verwachsen zu sein scheint, denn er macht sich auch im rasendsten Laufe nicht mit demselben zu schaffen, faßt kaum den Zügel, widmet seinem Gange keinen Blick und lenkt und tummelt und parirt es doch spielend und blitzschnell in den schwierigsten Wendungen. Nach dem jubelnden Gruß, den die bunte Schaar, etwa 75 Pferde stark, dem Publikum gebracht hat, stiebt sie wieder davon bis auf einen Kuhhirten, einen Mexikaner und einen Indianer, welche die Bahn im Wettlauf umreiten, wobei der Cowboy siegt. In der nächsten Nummer tritt die „berühmte Schützin,“ Frl. Annie Oakley, auf, eine schlanke junge Dame in einem Costüm à la Regimentstochter, die mit beneidenswerther Sicherheit und auf alle mögliche Arten ein paar Dutzend in die Luft geworfener Glaskugeln erlegt. Ihr folgt der Pony–Postreiter, welcher uns veranschaulicht, mit wie rasender Eile in good old Colony times die Prairiepost besorgt werden mußte; der Pferdewechsel dauerte noch keine halbe Minute und so ein wilder Postritt ging 50 englische Meilen weit ohne Aufenthalt und ohne Wirthshaus! Die etwa im Zuschauerraum anwesenden Landbriefträger der Reichspost werden ihren Collegen mit geheimem Schauder beobachtet haben. Der hieran sich anschließende Ueberfall eines Auswandererzuges durch Indianer bot zwar ebenso wie der Angriff auf die Deadwood–Postkutsche ein sehr lebendiges, buntes Bild, ist aber schon aus den Vorstellungen früher in Europa erschienener Indianer und Trapper bekannt. Der Zweikampf sodann zwischen einem Cowboy und einem Indianer, welcher mit der Scalpirung des Letzteren endigt, wird zwar im Programm mit nichts Geringerem als mit dem Zweikampf der Horatier und Kuratier verglichen, ist aber in dieser Darstellung zu episodenhaft, um ernstlich zu interessiren. Die Glanznummer des Programms ist das Schaureiten der Cowboys. Das ist wirklich ein Stück Wildniß und Wildheit. Die durch Schreien und Pfeifen wild gemachten kleinen unscheinbaren aber ausdauernden und schnellen Mustangs werden mit dem Lasso gefangen, dann trotz allem Bocken und Schlagen gesattelt und nun beginnt ein Kampf zwischen Mensch und Pferd, der athemraubend interessant ist. Beide beobachten sich Auge in Auge, der Reiter sucht in den Sattel zu gelangen, das Pferd ist bemüht, dies zu verhindern. Es dreht und wendet sich wie ein Aal, steigt hoch auf, wirft und schnellt sich empor, — so daß oft Minuten vergehen, ehe der Reiter den Steigbügel erhascht und den Sattel erreicht. Und dann beginnt der Kampf erst recht. Wie ein Stahlbogen biegt sich der Rücken des Pferdes, vorwärts, rückwärts schleudert es den Reiter und schüttelt ihn, daß die Haare fliegen — vergeblich, der Mensch siegt, nach einer Weile hört das Pferd endlich auf zu toben und giebt sich bezwungen. Diese aufregende und äußerst gefährliche Scene bildet den Höhepunkt der Vorstellung und das charakteristischste Moment des Lebens im Wilden Westen, wie die Wild West Company Première ein sehr guter war und es wohl auch bleiben wird, denn für die Romantik des Indianer– und freien Reiterlebens haben wir doch alle noch eine geheime Sympathie, wenn auch die Zeiten längst vorbei sind, wo wir mit dem „Lederstrumpf“ und dem letzten Mohikaner gemeinsam Heldenthaten verrichteten.

G. W.

English | German

Meitzener Tageblatt

Meitzen, June 3rd/90

[1]

Buffalo Bill's Wild West in Dresden

At the present time, it is but a small step to pass from the Grunaer Strasse to the prairies of the Wild West; wilderness and the white man's culture are separated by an enclosure in the form of a mere plank, which the medium of that culture, known as "money," enables us to surmount with ease. However, once on the other side, we perceive that the wilderness has already undergone a considerable process of civilization. Here, German brewers and American pastry chefs reach out to offer each other fraternal greetings, the tents of the cowboys could have come from a German military store–room, and even one of the most recent achievements of our civilization, jute, is no longer a material that is alien to the tapered wigwams, adorned with naïve paintings, of the Indians.

One of the obvious shortcomings of the Wild West enterprise is that the external get–up of the Indian camp has not been made to look more interesting. Quite apart from showing fine scalps and other pelts, an effort could have been made to bring together an abundance of old Indian weapons and a display of Indian artefacts, in the manner followed, mutatis mutandis, by those exhibiting in the Singhalese exposition. The Indian women produce attractive pottery, items made with feathers and beadwork, and are highly regarded in America as tapestry weavers. None of this is to be found in the Wild West show, and the result is a lack of the atmosphere that we would really have expected to find in the Indian scenes. These take place within the inner enclosure, in a gigantic arena accommodating at least four to five thousand spectators and encompassing a quite respectable stretch of prairie. This too shows traces of our civilization, as frequently to be seen in many towns throughout Saxony, for it is thoroughly sprinkled with water before the start of the spectacle!

At the entrance, a musical band, decked out in cowboy costume, plays its tunes; located in the middle is a somewhat problematic piece of scenery, which is presumably meant to represent a log cabin; and the back part is bedecked with an enormous green curtain. This divides quite suddenly, and with wild shrieks and yells a colorful band of Arapaho Indians bursts onto the scene, followed by a pack of cowboys, then more Indians, and after them another group of cowboys, and so forth, who gallop at breakneck speed up to the front row of the stands and swerve at the last minute to form up in lines before it, one behind the other.

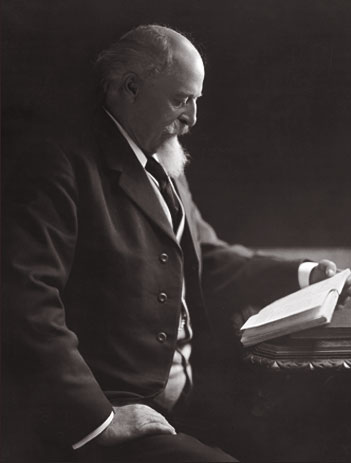

The Indians' clothing is as colorful as the cowboys' attire is colorless; one might more accurately speak of their costumes rather than their clothes, since some of the former are naked up to their hips and again from their waist up to their neck; after all, yellow and red body paint cannot be discerned under layers of clothing. Several superb specimens of manhood supplement this national costume with magnificent feather headdresses. Amongst those sallying forth, we saw four young ladies of the backwoods, graceful apparitions, one of whom was clothed in buckskins, the authentic material of the wild west, whilst the others wore civilized riding attire. Even Buck Taylor, the "king of the cowboys," a magnificent rider as tall as a tree, with a shock of long flowing hair, was dressed in a simple fashion; but the hero of the day, Buffalo Bill, wore a fantastic leather jerkin, embroidered with silk, and rode a sinuous, rather elegant white horse with a lightness and elegance the like of which we have never seen before in any circus. He is the epitome of the hero in popular tales of cowboys and Indians, no longer young but still unbowed, a ravishingly handsome warrior imbued with inborn charm and grace, albeit not lacking in a certain theatrical affectation, who seems in the true sense of the term to have developed a deep liaison with, and understanding of, horses, for he has no trouble in riding them even at the most breakneck speeds, scarcely uses the reins, pays no heed to where he is going, and steers and gambols and brings his steed to a halt in a playful way, quick as a flash, even in the most difficult maneuvers.

Following the shout of jubilation with which the colorful group, some 75 horses strong, greeted the crowd, it rushed away, leaving just one cowboy, one Mexican and one Indian engaged in a race on horseback around the arena, which the cowboy won. The next number featured the "celebrated sharpshooter," Miss Annie Oakley, a slender young woman in a costume redolent of something out of Donizetti's opera "The Daughter of the Regiment," who succeeded, with enviable self–assurance and in every possible way, in shooting down a couple of dozen glass balls thrown up in the air. She was followed by the Pony Express rider, who illustrated to us the way in which, at breakneck speed, in "good old colonial times," the prairie post had to be delivered; the change of horses took less than thirty seconds, so that it was possible, by means of this whirlwind postal ride, to cover no fewer than 50 miles without rest or refreshment! One may be sure that any of the spectators present who are employed as postmen by the German Imperial Postal Service will have shuddered to themselves as they observed their counterparts.

Then came the attack by Indians on a migrant wagon train; this presented a very lively and colorful spectacle but, like the attack on the Deadwood stagecoach, is something that is already familiar to the public in Europe from shows previously presented by Indians and trappers.

The ensuing duel between a cowboy and an Indian, culminating in the scalping of the latter, is described in the program as a contest comparable with the clash between the Horatii and the Curatii, but in this performance it was too episodic to be of any serious interest.

The star attraction of the program is the display of virtuoso equestrianism presented by the cowboys. This is, in reality, a combination of wilderness and wildness. The small, speedy mustangs, nondescript yet resilient, driven to a frenzy by shouting and whistling, are lassoed and then, despite all their bucking and kicking, saddled up, following which a struggle begins between man and horse that takes your breath away. They observe each other, eye to eye; the rider tries to get into the saddle, and the horse strives to stop him from doing so. It twists and turns like an eel, rises up, hurls itself earthwards like a flash of lightning, writhes, doubles up and spins upwards again, so that often minutes pass before the rider manages to catch the stirrup and succeeds in getting up into the saddle. And then the contest begins for real. The horse flexes its back like a steel arch; it flings the rider back and forth and shakes him so that his hair flies all over the place—but in vain: the human being emerges victorious, and after a while the horse finally ceases to rampage and acknowledges that it is beaten. This exciting and highly dangerous scene forms the high point of the spectacle and the most characteristic moment in the life of the wild west, as presented to us by the Wild West company. In and of itself alone, it warrants the price of a ticket to see the spectacle, which proved at its premiere yesterday to be, and will doubtless remain, a highly enjoyable show, for we must each of us admit that the romanticism of life amongst the Indians and frontiersmen holds a secret fascination, even though the times are long gone when deeds of heroism were performed as featured in James Fenimore Cooper's "Leatherstocking Tales" and "The Last of the Mohicans."

G.W.

Note 1: Buffalo Bill's Wild West performed in Dresden, Germany, June 1-17, 1890. [back]